About

Malvaux

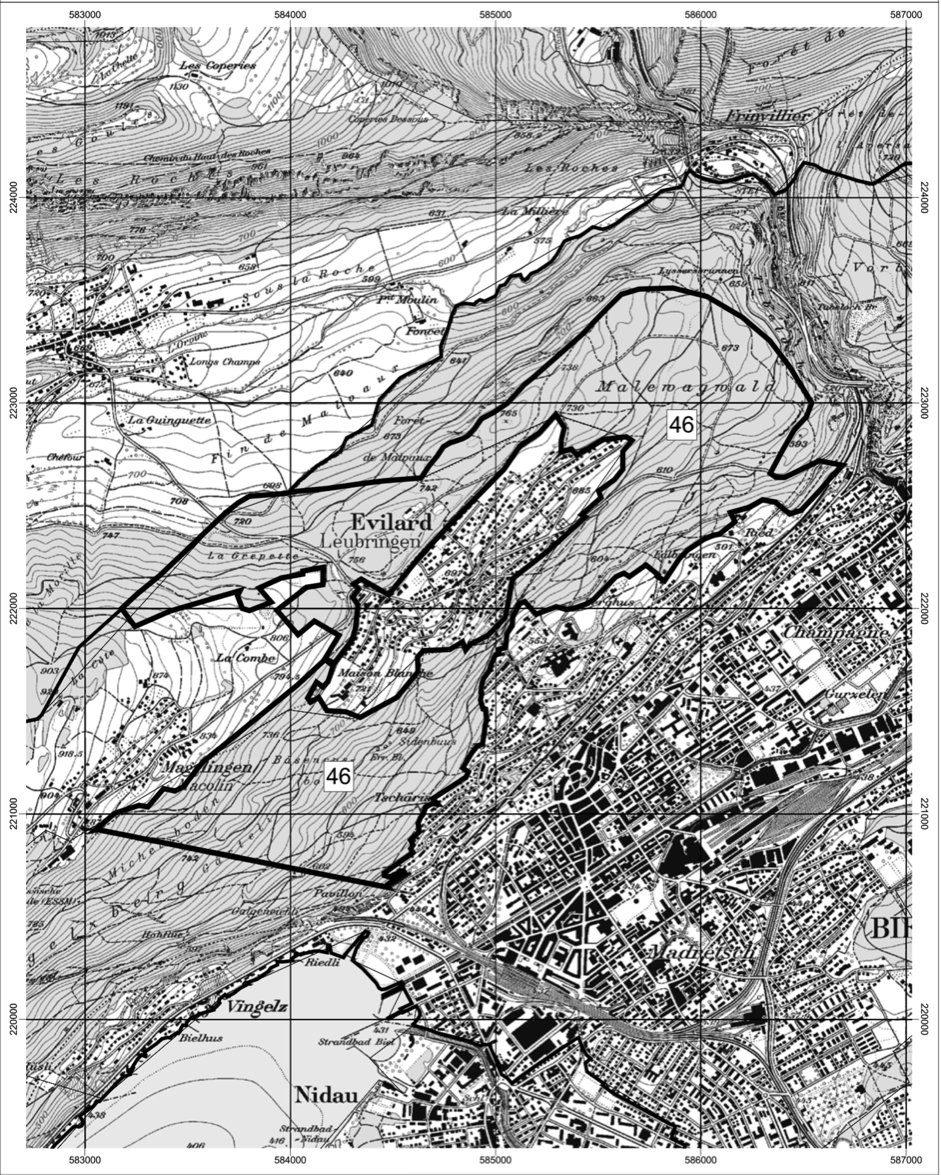

Malvaux is the name given to the forest that stretches along the north-western slopes of the city of Biel/Bienne to the villages of Macolin and Evilard. This forest is located on a 300-meter-high slope of the Jura mountain range. We’ve chosen to name the ecomatic exploration center in this way, to remind ourselves that it’s first and foremost an encounter with the forest environment that we’re talking about.

Why does it seem important to go and ask questions in the forest, to go to this school of life? How does it move us? What practices and narratives does a forest suggest to us as partners, as opposed to urban environments or dance studios? What does the forest teach us about ourselves? What are its gifts and those of dancing in seasonal cycles? Here we are, where nothing exists without the interweaving of others, where each center is a center among other centers, where no name holds together without the weaving of its collaborations, symbioses and competitions. Here we are among multiple temporalities, among myriads of growths and putrefactions.

Our center has no walls. Its roof is the sky, with rain, mists, reflections of the sun on foliage, winds and stars. Its soil is a living humus that extends deep down, full of odors, rough, soft and pungent. Trees and vegetation envelop us. Here we experience a distance from the view, from the balcony, from having a view on, from looking at the world as if on a painting or a set. We’re moving away from the Renaissance perspective of knowledge. We return to plural, mismatched, reinvented, felt perspectives. We’re in, amongst, breathing together in this orchestra of the living. Among squirrels, beeches, firs, mosquitoes, limestone, beetles, clay, ivy, boulders, green woodpeckers, hinds, winds, foxes and oaks. Other human activities include the parcours vita, footpaths, hermitages, forest schools, cemeteries, huts, national roads and forestry companies. Among our feelings, our perceptions, our imaginations, our bodies and their movements, among us in groups, in communities.

Ecosomatics

In naming our practices ‘ecosomatic’ we wish to participate in the development of a field at the crossroads of the arts, ecology and society. It’s a recent name for a relationship with living things that is not new in itself, but one that needs to be recreated, like reactivating lost paths. Above all, it’s about relationships, understanding ourselves as part of the interactions and interdependencies of living beings other than humans. We support the urgency of embodied, situated knowledge, of which our bodies, understood in these local ecologies, become both receptacles and channels. We work for the future of the Earth, and we defend, feel, live, create and love our belonging to the Earth system.

In Ecosomatic. Thinking ecology through gesture (2019) Marie bardet, Joanne Clavel and Isabelle Ginot define the field of ecosomatics as “a field of study and practice in which the rejection of any separation between the body and its Others, and a sense of self as a milieu for other living beings – whose presence makes our own life possible – are at work”. They define four challenges for these practices: the power to generate both theoretical and experiential knowledge “that thinks of the body as soma- indivisible ensemble of physical, sensitive and mental corporeity, inseparable from its environments”; “to refrain from separating environmental issues from social and political ones” ; to de-prioritize practices, giving as much importance to knowledge of the body, of the intimate, of the subjective, as to mainstream knowledge; and finally, to think of the work of choreography as a process of emancipation and practical action on ways of being and making the world. Eco-somatics aims to “reinscribe bodily subjectivity in the continuity of its relationships with the living”. These disciplines, like the somatic practices that emerged in the West at the end of the 19th century (Alexander, Feldenkrais, Eutonie, Rolfing, relaxation, holistic gymnastics, Body-Mind Centering, perceptive pedagogy), call into question the philosophical dichotomies that founded modernity in the West, such as the mind-body division, or the “naturalist” thinking that divides nature and culture, to use Philippe Descola’s concept. It adds an ecological dimension that acknowledges our interdependence with the Earth system, which we have known to be in peril since the 1970s. Eco-somatics observes the interdependent relationships of body, thought, affect and emotion, and the relationship of continuity between bodies and environments, as the state of environmental presence reminds us: our presence is always situated. In her book Movements. Ecopolitics of dance (2023) Emma Bigé refers to the Greek verb haptomai , which designates the median way of touching, and notes that in touching an object “the subject of the activity is at the same time the one to whom the activity happens”. She poses the same question for the act of dancing, revisiting Steve Paxton’s La Petite Danse (1967), which involves standing still to observe the micro-movements of readjustment that run through our bodies in negotiation with gravitational force. This practice places us in bodying, or, in the words of choreographer and philosopher Erin Manning, “the body-in-the-making”.